노벨상 제외한 세계 저명한 상 모두 받은 세계적인 석학

조직공학과 약물전달시스템 개발에 창의적 아이디어 도입 약 700여편 학술논문 발표

좋은 아이디어로 벤처기업 30여개 만들어 보급

켐브리지 로열 소네스타 보스톤 호텔에서 탄생 70주년 맞아 기념 컨퍼런스 열어

밥 랭거(Bob Langer) 교수는 MIT공대 석좌교수로 미국 National Academy(과학, 공학, 의학) 회원이다. 화학공학적 기반에 생명과학, 특히 조직공학과 약물전달시스템 개발에 창의적 아이디어를 많이 도입하여 약 700여편의 학술논문을 발표하였다. 노벨과학상 이외의 세계적으로 저명한 모든 상은 다 받았다. 매년 노벨생리의학상 후보로 거론되고 있을 정도로 미국내 뿐만 아니라 전세계적으로 잘 알려져 있는 과학자이다. 좋은 아이디어로 벤처회사를 30여개 만들어 보급하였다. 노벨사이언스 편집위원장인 성용길 미국 유타대학 연구교수와 김성완 석좌교수는 밥 랭거(Bob Langer) 교수의 탄생 70주년을 맞이하여 2018년 9월 7일부터 9일까지 (3일간) 미국 매사추세트주, 켐브리지(Cambridge)의 로열 소네스타(Royal Sonesta) 보스톤 호텔에서 열린 기념 컨퍼런스에 참여하고 밥 랭거(Bob Langer) 교수와 인터뷰를 했으며 행사 전반에 관한 취재도 했다. 밥 랭거(Bob Langer) 교수의 걸어 온 발자취와 부인 라우라 랭거(Laura Langer)와 연구생활을 소개한다.

|

| Dr. Robert S. Langer and his wife, Laura, attend the 2012 International Achievement Summit in Washington, D.C. |

Dr. Robert Langer and his wife, Dr. Laura Langer, in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Langer met his wife at MIT in 1984. She was the roommate of one of his postdoctoral associates and completing her own MIT Ph.D. in neuroscience. They married in 1989.

Listen to this achiever on What It Takes

What It Takes is an audio podcast on iTunes produced by the American Academy of Achievement featuring intimate, revealing conversations with influential leaders in the diverse fields of endeavor: music, science and exploration, sports, film, technology, literature, the military and social justice.

I was a chemical engineer on the one hand, and then I would be exposed to medicine. I would have two different disciplines. They were so different. You'd think 'Well, you could combine them,' and that would give me ideas that nobody at that time had -because nobody else had that kind of background.

The Edison of Medicine

DATE OF BIRTH : August 29, 1948

|

At age of 11, Bob Langer became fascinated with the magic of chemistry after receiving a chemistry set.

Robert Samuel Langer, Jr. was born and raised in Albany, New York. His father was a business-man who ran a billiard parlor in nearby Troy, New York, and then a liquor store in Albany. As a youngster, Robert enjoyed magic tricks, and when he was given a Gilbert chemistry set at age 11, he delighted mixing the colors and observing the chemical reactions. Soon he was making rubber and synthesizing simple plastics. At the Milne School in Albany, he excelled in math and science, and he was encouraged by his family to study engineering in college. As a freshman at Cornell University, he most enjoyed his chemistry class, and decided to major in chemical engineering. He graduated from Cornell in 1970 and pursued graduate studies at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)As Langer was working towards a doctorate, the U.S. passed through a severe gasoline shortage. American industry was eagerly searching for ways to increase fuel efficiency, and chemical engineers were in high demand. Most of Langer’s classmates headed for careers in the energy industry. Langer himself received 20 offers from oil companies, including Shell and Chevron, and four from Exxon alone, but he couldn’t interest himself in fuel technology. While studying in Cambridge, he had developed a chemistry and math curriculum for inner city school children, and he was still looking for a career where he could help others more directly than he felt he could do in the oil industry.

Langer applied for research positions at 40 colleges and universities without hearing back from any of them. Nine research grant proposals he wrote were rejected. Then he wrote to hospitals and medical schools to see if they could use a chemical engineer, but he received no offers. Finally a friend in Cambridge recommended he contact Dr. Judah Folkman, a Harvard professor who was also chief of surgery at Boston’s Children’s Hospital. At the time, very few chemical engineers were working in surgical labs, but Dr. Folkman was pursuing an unorthodox approach to cancer research and was willing to employ postdoctoral fellows without conventional medical or biological training. Folkman believed that the spread of cancer and the growth of tumors could be controlled if angiogenesis, the process by which new blood vessels are created, was arrested. He set Langer the task of finding substances to inhibit the creation of new blood vessels.

Judah and Paula Folkman with Robert and Laura Langer. Dr. Folkman was a mentor to the next generation of scientists, training top researchers such as tissue engineering pioneer Robert Langer. (Courtesy of Bob Langer)

While in Folkman’s lab, Langer pursued a second avenue of research. He was searching for polymers that would permit the gradual timed release of medication within the body. Other scientists had considered this idea and abandoned it as impossible, but Langer believed it could be done and undertook the painstaking process of eliminating possible formulae. In the first two years, he tried more than 200 variations, before finding a technique for modifying polymers that would slowly release the molecules for drug delivery. The same technique facilitated the testing of substances for inhibiting angiogenesis.

Two years into this work, Langer was called on to give a talk about his research for a conference of polymer chemists and engineers, but he was met with incredulity. He fared no better when he submitted research proposals to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). His first nine research grant applications were turned down. From his first publication on angiogenesis, nearly 28 years would elapse before the Food and Drug Administration approved the first anti-cancer drug based on this work.

|

|

|

|

After completing his postdoctoral work, Langer applied for positions in chemical engineering departments, but met a cool response. While the biologists at NIH had felt that, as a chemical engineer, Langer couldn’t know anything about biology, much less cancer, the chemical engineering faculty at most of the universities where he applied believed his research belonged in the biology department or the medical school. Finally he was offered a post in the Nutrition and Food Science program at MIT, but in his first years at MIT, even this position was precarious.

Since there was little interest in his work in the academic and institutional worlds, he set out to interest the private sector. He began writing patents for his discoveries, in the hope that he could license them to pharmaceutical companies that would finance their further development and bring them to market, where they could benefit patients directly.

|

2003: Dr. Robert S. Langer is one of the ten most cited individuals in history and is the most cited engineer ever.

His first patents concerned polymer systems for controlled release of macromolecules. Again, he had difficulty persuading others of the value of his ideas. The reviewers at the patent office didn’t believe controlled release would work. His application was turned down five times between 1976 and 1981, and the attorney handling his application advised him to give up. When Langer demonstrated the effectiveness of his work, the patent office replied that his work was nothing new. In the end, to prove his work was original, he procured affidavits from the authors of a 1979 paper who had flagged his approach as being far out of the mainstream.

With patents in hand, Langer applied to NIH for a grant to support developing biodegradable polymers for the delivery of brain cancer drugs, but the reviewers did not believe such polymers could be synthesized. Langer’s grant applications were rejected many times in the years to come.

Once he had secured his patents, Langer still had difficulty finding interested companies to pursue his ideas. In 1983, International Minerals & Chemicals licensed one of his patents, and hired him as a consultant for a project using polymers to deliver animal hormones. The following year, Eli Lilly & Co. signed him for a similar project with human hormones, but when the first trials were unsuccessful, these large businesses quickly lost interest. In 1985, Langer made a deal with a much smaller company, Nova Pharmaceuticals of Baltimore, to license one of Langer’s patents for the delivery of brain cancer treatment. Unlike the larger companies, Nova was fully committed to innovation. Langer realized that working with small, narrowly focused enterprises was the best way to advance his ideas in the marketplace.

|

ven before his success with Nova, Langer had been approached by venture capitalists about starting a company of his own, and in 1987, he and a colleague, Alexander Klibanov, founded Enzytech. The company produced and brought to market a microsphere drug delivery system. Products based on the principles Langer developed have since been used to treat alcoholism, narcotic addiction, diabetes and other diseases. Enzytech was later merged with another company to form Alkermes.

Jay Vacanti, a surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital, interested Langer in combining three-dimensional synthetic polymer scaffolds with living cells to create new tissues and organs in the laboratory. At the time, Langer was unable to get government grants for this research, so Langer began to look for commercial funding. In 1988, he started a second company, Neomorphics, to produce biocompatible materials for tissue growth. Like Enzytech, Neomorphics was later acquired by larger concerns, Advanced Tissue Sciences and Smith & Nephew. As his ideas achieved success in the marketplace and acceptance in academia, Langer’s position at MIT became more secure and he was given a full professorship.

Langer displays one of the implant devices he has invented to deliver medication. He is a “pioneer of many new technologies, including controlled release systems and transdermal delivery systems which allow the dispensing of drugs or extraction of analytes from the body through the skin without needles or other invasive methods.”

Whereas other researchers tried to find medical applications for existing plastics, Langer identified the qualities he was looking for and synthesized new materials to meet the need, creating a new family of biodegradable polymers, the polyanhydrides. In 1992, Langer founded Focal to produce biodegradable materials for sealants and for the prevention of surgical adhesions. The following year saw the creation of two new enterprises: Enzymed, which produced combinatory pharmaceuticals; and Acusphere, which developed imaging agents with porous microsphere technology. The first two of these concerns were also merged with larger companies, and the third became a publicly traded company, continuing Langer’s winning streak in the business world.

|

|

In the 1990s, Robert Langer established a new model of research and development. If a discovery in his laboratory is a genuine breakthrough that offers the possibility of multiple applications, and an exclusive patent can be obtained, and if students or postdoctoral fellows of Langer’s have worked with the technology for five years or more, Langer encourages them to start a new company to develop the idea if they are interested. By collaborating with his students in the founding of these businesses, Langer mentors them as both scientists and entrepreneurs. At first, this practice was controversial, but these startups have created new treatments for cancer, heart disease and other deadly ailments, while providing employment to thousands.

After the initial startup period, Langer often withdraws from the enterprise, although sometimes he remains on board as a paid advisor or board member. When a discovery is licensed from MIT, the profits are split between the department, the university and the inventors. MIT scientists are permitted to take equity stakes in the companies that employ their discoveries, but they cannot own shares in businesses that provide research grants to their laboratories, and they cannot serve as executives of outside firms, although they may serve as paid advisors.

|

|

In 1996, the FDA approved the use of Langer’s controlled-release drug delivery system for the treatment of brain cancer. In the next few years, Langer and his students were responsible for an almost continuous stream of startups, bringing new inventions and discoveries to market at a dizzying pace.

Langer and a former postdoctoral student, David Edwards, now a professor at Harvard, created Advanced Inhalation Research in 1997 to develop pulmonary drug delivery. In 1998, Langer and Jay Vacanti founded Reprogenesis to build polymer scaffolding for regenerative tissue. This technique, once thought controversial, is now the basis of regenerative medicine, which produces artificial skin for patients with severe burns or skin ulcers. The same year, Langer started Sontra Medical (later renamed Echo Therapeutic) to provide transdermal drug delivery.

Dr. Robert S. Langer is one of the world’s eminent biotechnology researchers, especially in the field of drug delivery systems and tissue engineering. He is the youngest person in history — at age 43 — to be elected to all three American science academies: the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. Langer has received more than 220 major awards, and he is one of four living individuals to have received both the U.S. National Medal of Science and the National Medal of Technology and Innovation.

In 1999, Langer formed MicroCHIPS (with his former graduate student, John T. Santini, Jr.) to develop silicon-chip-based drug delivery, and Transform Pharmaceuticals (later acquired by Johnson & Johnson) for polymorph crystallization. These were followed in the next three years by Combinent Biomedical Systems for transvaginal drug delivery, Pulmatrix for inhaled medication, and Momenta Pharmaceuticals for complex sugar-based therapeutics. Momenta’s sugar-sequencing tools have been used to create more effective blood thinners. In the midst of this success, the FDA finally approved the use of an anti-cancer drug based on the research Langer had first published 28 years earlier, as a postdoctoral student in Judah Folkman’s surgical laboratory.

|

|

Meanwhile, Langer and his students continued to break new ground in medical research. In 2004, his new company, Pervasis, introduced new therapeutics for vascular healing. The following year saw the creation of three more businesses based on Langer’s work. Arsenal Medical, which was founded to develop nanofiber-based drug delivery, eventually split into two companies, Arsenal Vascular and 480 Biomedical, which produces resorbable scaffolds for tissue growth. In Vivo Therapeutics produces scaffolds specifically for spinal cord therapy. Not all of Langer’s ventures are concerned with life-threatening disease or crippling injury. Living Proof develops hair and skin care products, including a hair-thickening agent based on a material Langer’s lab originally created to treat prostate and ovarian cancer. Langer oversaw the creation of three new enterprises in 2006: Semprus BioSciences, for medical device coatings; BIND Biosciences for targeted nanoparticle-based therapeutics; and T2 Biosystems for nanoparticle-based diagnostics. The following year saw the birth of Selecta Biosciences for targeted nanoparticles. In 2008, Langer opened Taris Biomedical for urological drug delivery, and Seventh System Biosystems, which produces a microneedle patch for drawing blood outside of medical facilities. This work, along with a controlled-release polio vaccine developed in the Langer Lab, has been financed by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for use in the deve

|

|

loping world. In 2009, Langer and a Johns Hopkins professor (and former Langer student), Justin Hanes, started Kala Pharmaceuticals to provide mucosal drug delivery.

The awards are the highest honors bestowed by the United States Government upon scientists, engineers, and inventors. (AP/Charles Dharapak). Langer’s latest ventures include ModeRNA for modified messenger RNA delivery, and Blend Therapeutics, for combination medicines. In 2012, MicroCHIPS completed the first human trials of a wirelessly controlled chip that delivers a drug to stimulate bone formation in osteoporosis patients. A silicon chip with doses of the drug stored in individual reservoirs, each capped with a thin film of platinum and titanium, it releases its contents in response to wireless electric signals. Langer predicts that sensors and drug delivery function will someday be incorporated in a single implantable device which can release drugs in direct response to signals from the body. That same year, Robert Langer received the Priestley Medal, the highest honor of the American Chemical Society. It was the first time in 65 years that the award was given to a chemical engineer, and the first time it was given to a bioengineer. In 2013, he received the newly created Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences. Financed by a group of entrepreneurs, including Google’s Sergey Brin and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, the award amounts

to $3 million per individual recipient, making it the largest prize purse in science, more than twice as much as that shared by multiple Nobel Prize recipients in any category. Two years later, he was awarded the 2015 Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering, for his revolutionary leadership “at the interface of chemistry and medicine.”

|

|

Today, Robert Langer occupies an unparalleled position in science, business and education. He is the David H. Koch Institute Professor in the Department of Biochemistry. An Institute Professorship is the highest honor a faculty member can hold at MIT; Robert Langer’s professorship was endowed by MIT graduate David H. Koch of Koch Industries. Langer Laboratory at MIT — with over 100 students, postdocs and visiting scientists at any one time — is the world’s largest academic biomedical engineering laboratory.

By the end of 2013, Robert Langer had authored more than 1,200 publications. More than 1,025 patents had been issued in his name or were pending; more than 250 companies had licensed or sublicensed Langer Lab patents. His work has been cited in scientific publication more than 170,000 times, more than that of any other engineer in history. In 2015, his accomplishment was honored with the £1 million Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering.

|

|

The Langer Laboratory has served as an incubator for 40 independent companies. Dr. Langer spends roughly one day a week working with the businesses he helped start. He serves on the boards of 12 of these and is an informal advisor to four. His entrepreneurial activities have made him a millionaire, but his primary motivation remains improving the health of men, women, and children around the world. In recent years, Langer Lab has been working with the U.S. Army on a regenerative tissue project for wounded soldiers.

It has been estimated that the lives of as many as two billion people have been touched by the technologies created by Robert Langer and his research teams. Many of his former students now lead companies or laboratories of their own and advise governments on medical technology. As a colleague has said of Dr. Langer’s students, “They come away thinking that nothing is impossible.”

□Langer 교수의 인터뷰

MIT 랭거 교수는 42년간 생체재료 분야에서 연구해 왔다. 이번 심포지움에서 흥미로운 연구결과들을 발표한바 있고, Nature Materials에서 인터뷰했던 내용(원문)*을 발췌하여 소개하기로 했다.

|

|

Q) How did you become interested in working with biomedical materials?

A) In 1974, I had just begun a postdoctoral position with Judah Folkman at Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and I needed to solve a problem: to isolate what would be the first angiogenesis [growth of blood vessels] inhibitor. To do this, I wanted to develop a corneal assay for stopping blood vessel growth in a rabbit; part of this involved the creation of a polymer system that could be embedded in the cornea to continuously release macromolecules that were angiogenesis inhibitors for many months. In 1976, we published this research in Science1 and since then the area of angiogenesis inhibitors has become an enormous field. Over 1 million people use such inhibitors every year to treat cancer or macular degeneration, a leading cause of blindness.

Q) What are your principal research interests in the biomaterials area at the moment?

A) We continue to work in drug delivery and controlled release. Some of the newer things we are doing in drug delivery include creating nanoparticles that are targeted to specific cells in the body, and the delivery of new molecules, such as siRNA [small interfering RNA], that can be used to turn genes off. We are also creating specifically designed nanoparticles containing DNA to allow gene therapy on many different cell types. Finally, we are carrying out work on tissue engineering-combining materials and cells to create new tissues and organs in the body. This work is leading to the creation of new skin and other tissues.

Q) What work are you most proud of from your time working on biomaterials?

A) There are many areas I’m proud of. One of these is our early discovery in 1976 of how polymers could be used to continuously release macromolecules. Another area is diseases. A third one is tissue engineering. In 1983, Jay Vacanti and I had an idea that if we designed polymer fibers in the right way, cells might be able to organize themselves on the fibers to create organs and tissues - and that turned out to be true. We’re proud of this work because these studies showed that you could make three-dimensional polymer scaffolds and use them in such a way to help organize cells to make tissues. This approach has been widely used in academia and industry as a cornerstone of regenerative medicine. I believe our 1993 Science paper on this topic has been cited over 2,000 times3. Some tissues, clinically based on this concept, are already available — such as skin — but there are still many others that would be good to make, for example, spinal cords, livers, pancreases, and hearts. So we continue to work on all of the aspects that are required: cell biology, immunology and materials. The more complex organs -heart, liver, and kidney - are a bigger challenge. Increased complexity often means more cell types, which increases the difficulty of making the tissues or organs.

Q) How do you approach the challenge of achieving this complexity?

A) Materials are just one part of it. One might want to have a vascular supply, so one could use microfabrication as a manufacturing technique to build in micro-vessels. You may want to synthesize highly elastic, strong biomaterials because some tissues, such as the heart, require elasticity. Recently, Lisa Freed, I and our colleagues showed that this approach could be useful in tissue engineering by making an accordion like polymer structure seeded with heart cells that could create new heart tissue.

Q) What has been the most impressive development in tissue engineering in the past five years?

A) The whole area of stem-cell biology is one of the most exciting developments: trying to understand how to control stem-cell behavior, and how you can convert regular cells into stem cells — such as the IPS [induced pluripotent stem] cells. These kinds of areas are very important. Though researchers have achieved a lot, the way they have achieved this is generally by using viral vectors[to deliver genetic material into cells]. I hope the work that we and others are doing will enable a way to do these steps with non-viral vectors. We have been collaborating with Rudy Jaenisch at the MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), and he is a pioneer with IPS cells, although he started with viral vectors the same as everyone else. We have created materials that are very potent at gene therapy and so we hope we will be able to use these materials to replace viral vectors and this, of course, would be safer. In particular, Dan Anderson and others in our lab are synthesizing new polymers that can deliver genes very effectively and yet are still quite safe.

Q) What important factors do you keep in mind when designing biomaterials?

A) There are several factors. The materials themselves can be an inspiration - you might get an idea from what the tissue is like; what the strength and elasticity should be; what the degradation should be; whether you want a more complex microstructure because you might be using multiple cell types. One example that requires a more complex microstructure is the liver, which has five cell types plus a complex network of blood vessels. To work on this, we have been collaborating with Jeff Borenstein at Draper Labs using microfabrication technologies to create a micro-vascular structure.

*원문: Nature Materials | VOL 8 | JUNE 2009 | www.nature.com/naturematerials

|

□Bob Langer 70th Birthday Celebration

September 7-9, 2018 – Cambridge, Massachusetts

미국 MIT공대 Bob Langer 석좌교수 탄생 70세 기념 9월 7일–9일 (3일)간

심포지엄 컨퍼런스 개최 (Boston)

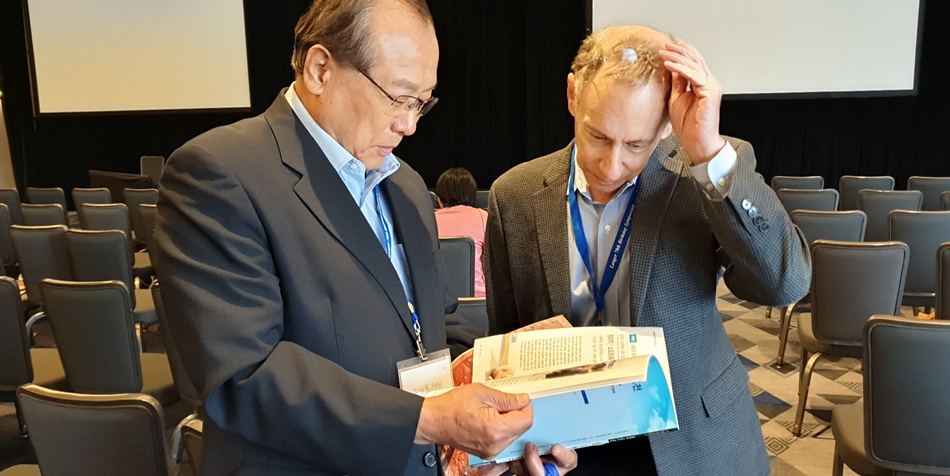

밥 랭거(Bob Langer) 교수의 탄생 70주년 기념 컨퍼런스는 2018년 9월 7일부터 9일까지 (3일간) 미국 매사추세트주, 켐브리지(Cambridge)의 로열 소네스타(Royal Sonesta) 보스톤 호텔에서 개최되었다. 이 행사에는 세계적인 과학자, 현재 및 과거의 밥 랭거 연구소의 석학 멤버 500여명이 참석했다. 그 중에는 공동연구자와 친구들이 과거 42년여 동안 같은 연구분야 에서 과학업적과 밥 랭거 탄생 70주년을 기념하기 위하여 컨 퍼런스에 초청되었다. 이번 행사에 유타대학교의 김성완 석좌교수(사진), 유타대 출신 성용길 노벨사이언스 편집위원장 (동국대 명예교수) 등이 초청되어 행사를 취재하였다.

|

| 왼쪽으로부터 김성완 유타대 석좌교수, 밥 랭거 MIT 석좌교수, 성용길 본지 편집위원장 (한국노벨과학연구원 원장) |

이번 콘퍼런스와 심포지엄의 진행은 뉴저지주립대 Rutgers University의 Joachim Kohn 교수(좌장)의 사회로 시작되었으며, 진행 순서는 다음과 같다.

◆첫날, Friday, September 7th, 2018

4:00-6:30pm Registration and Check-in

5:00-6:30pm Reception with heavy appetizers

6:30-8:00pm Opening Ceremony

6:30-6:35pm Joachim Kohn Opening Remarks

6:35-6:40pm Bob Langer Welcome

6:35-6:45pm Laura Langer Introduction to the Event

6:50-7:10pm Nicholas Peppas and Michael Sefton, How Langer’s pre-1988 MIT days shaped the societal and economic impact of his work.

7:10-7:25pm Marsha A. Moses Langer’s years at Boston Children’s Hospital:

Dr. Judah Folkman’s Postdoc and the first Langer Lab

7:25-7:45pm Samir Mitragotri and Ali Khademhosseini Langer Lab: The Middles Ages

7:45-8:00pm Dan Anderson, Padmini Pillai, Malvika Verma The Langer Lab Today

8:00-8:05pm Sponsor Presentation by MIT Chemical Engineering Department

8:05-10:00pm: Reunion with dessert

◆둘째 날, Saturday, September 8th, 2018

8:15-9:00am: Breakfast

Session I

9:00-10:30am: Chairs: Dave Lynn and Chris Alabi “Polymers/Basic Science”

9:00-9:20am Keynote Speaker: Joseph DeSimone

“How Advances in Polymer Science Can Create New Business Categories”

9:20-9:30am Andreas Lendlein Driven by Vision-Transforming Polymers

9:30-9:40am Joachim Kohn/Kam Leong

The Impact of early polymer work in Bob’s Lab: Polyanhydrides, Polyphosphoesters and Tyrosine-derived Pseudo-Poly(amino acid)s

9:40-9:50am Howie Rosen Before Bob was Bob: The Birth of Polyhanhydrides

9:50-10:10am David Tirrell Special Guest Lecture

10:10-10:20am Shaoyi Jiang Biocompatible Zwitterionic Materials

10:20-10:30am Summary/Comments

10:30-11:00am Break

|

| 랭거 심포지움에서의 강연 장면 |

Session II

11:00am-12:20pm Chairs: Howard Bernstein and Jennifer Elisseeff

“Medical Devices”

11:00-11:20am Keynote Speaker: Josi Kost Sound Science and Beyond

11:20-11:30am Janet Tamada Why pioneers have arrows in their backs: Tales from developing the world’s first patient-use continuous glucose monitor

11:30-11:40am Jeff Karp Towards Accelerated Medical Innovation

11:40-11:50am Mark Prausnitz Microneedle technology for drug delivery: past, present and future

11:50-12:00pm Special Video12:00-12:10pm Dr. John Santini The Early Development of Nov

12:20-12:25pm Sponsor Presentation by Flagship Pioneering

12:30-2:00pm Lunch (provided)

Session III

2:00-3:00pm Chairs: Bob Linhardt and Giovanni Traverso “Out of the Box”

2:00pm-2:20pm Speaker: Colin Gardener Bob Langer: From graduate student to academic entrepreneur

2:20-2:30pm Ana Jaklenec Feeding the World

2:30-2:40pm Amir Nashat Living Proof: Polymers for cosmetic applications

2:40-2:50pm Yonathan Zohar Drug delivery to convince fish to reproduce

2:50-3:00pm Summary/Comments

3:00-3:30pm Break

|

Session IV

3:30-5:00pm Chairs: Debra Auguste and James Dahlman “Drug Delivery”

3:30-3:50pm Keynote Speaker: Justin Hanes Special Delivery: A Tribute to Bob Langer 3:50-4:00pm Dan Kohane Targeted and triggered drug delivery

4:00-4:10pm Akin Akinc Delivery of RNAi Therapeutics

4:10-4:20pm Dan Heller Targeting Targeted Medicines

4:20-4:30pm Paula Hammond Nanolayered Particles for Tissue Targeted Therapies

4:30-4:40pm David Edwards Digital Scent Therapy

4:40-5:00pm Summary/Comments

5:00-6:00pm Break 6:00-9:00pm Gala Dinner

6:10pm Chair: Margaret Wheatley Opening Statement

6:15pm Sponsor Presentation by Polaris Partners

6:20pm Brief comments Laura Langer

7:10pm Congratulatory Letters from VIPs presented by Elazer Edelman.

7:25pm Alex Klibanov and Mike Marletta Roasts/Talks

7:45pm Keynote Speaker: Henry Brem

8:00pm Elazer Edelman and Jordan Green Trivia Game

8:20pm Bob and/or Laura Langer Closing remarks

8:30-9:30pm Intermission

9:30-11:00pm After Party

|

◆셋째 날, Sunday, September 9th, 2018

8:15-9:00am – Breakfast

Session V

9:00-10:30am Chairs: Laura Niklason and Fan Yang “Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine”

9:00-9:20am Keynote Speaker: David Mooney Bob-Inspired Evolution in Tissue Engineering

9:20-9:30am Antonios Mikos Biomaterials-aided Mandibular Reconstruction Using in vivo Bioreactors

9:30-9:40am Gordana Vunjak-Novakovic, An Incredible Journey

9:40-9:50am Molly Stevens, Exploring the bio-material interface

9:50-10:00am Special Feature, Special Video, Feature of Langer Lab Alumni

10:00-10:10am Michael Yaszemski, A Long and Winding Road

10:10-10:20am Larry Brown Vision Restoration Following Optic Nerve Disease and Injury via Nose to Brain Delivery of an Amnion Cell Secretome

10:20-10:30am Summary/Comments

10:30-11:00am Break

|

Session VI1

1:00-12:00pm Chair: David Putnam. “Highlights of Bob's Career”

11:00-11:30am Keynote Speaker: Jay Vacanti Forty-One Years of Collaboration and Friendship 11:30-11:45am Bruce Zetter Robert Langer: Then and Now (and in-between)

11:45am-12:00pm Mark Saltzman. Bob Langer’s Contributions to Drug Delivery

12:00-12:05pm Sponsor Presentation by Modern Therapeutics

12:05-2:30pm Lunch and Poster Session

Session VIII

2:30-3:30pm Chair: Joachim Kohn “Closing Session”

2:30-2:45pm Lisa Freed. Bob’s Mentorship

2:45-3:00pm Cato T. Laurencin. Langer Lessons for Life

3:00-3:10pm Terry McGuire. Acknowledgement of Donors

3:10-3:15pm Joachim Kohn. Acknowledgement of Volunteers, Committee Members

3:15-3:30pm Bob Langer Closing Remarks

3:30pm: Adjourn

등의 순서로 진행되었다. 인상적인 것은 발표자나 질문자들이 서로 충분히 묻고 대답하는 것들이 보기가 좋았다. 자유토론 방식의 질의응답에서 아이디어를 찾고 문제점들을 해결하는 방안을 도출해 내는 것들이, 여기서 우리가 배워야 할 것으로 생각되었다.

우리나라 교육에서도 이제는 암기위주의 주입식 교육방식 보다는 자유롭게 토론하며 문제점을 발견하고 해결해 나가는 학습방식이 바람직할 것으로 생각된다. 각 세션(Session)이 끝날 때마다 정리하고 종합적으로 토론을 마무리해가는 것도 우리가 배워야 할 점이라고 여겨졌다. 시종일관 참여자 모두가 적극적이고 긍정적인 자세로 경청하고 질의 응답해 가는 것들이 아주 재미있었다.

참으로 밥 랭거는 연구업적도 많거니와 사업수단이 좋고 머리가 우수해서 세계적인 학자로 대접을 받고 있나보다 하는 생각이 들었다. Bob Langer 석좌교수의 최근 몇 년간의 연구업적을 취재하였다. 그리고 밥 랭거 교수의 수상실적을 정리하였으며, 그의 연구업적은 노벨사이언스 홈페이지에 게재하였다.

|

||

|

랭거 교수(우)에게 노벨사이언스 매거진을 설명하는 성용길 본지 편집위원장 (좌)

|

□ROBERT SAMUEL LANGER AWARDS(랭거의 수상 경력)

2018 Leadership Award for Historic Scientific Advancement

(American Chemical Society)

2018 Honoray Doctorate, University of Limerick, Ireland

2018 Honorary Doctorate, University of Illinois

2017 Named Number 1 Translational Researcher in the World

(Nature Biotechnology)

2017 Kabiller Prize in Nanoscience and Nanomedicine

2017 Honorary Doctorate, National Institute of Astrophysics, Optics and

Electronics, Mexico

2017 Memorial Sloan Kettering Medal for Outstanding Contributions

to Biomedical Research

2017 Honorary Degree, Gerstner Graduate School,

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

2017 Tetelman Fellow, Yale University

2016 Honorary Degree, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden

2016 Honorary Degree, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology,

Hong Kong

2016 Raymond and Beverly Sackler Award for Sustained National Leadership (Research!America)

2016 Benjamin Franklin Medal in Life Science (Franklin Institute)

2016 Irving Weinstein Foundation Distinguished Lecture Award

(American Association for Cancer Research)

2016 Honorary Degree, Carnegie Mellon University

2016 European Inventor Award, Non-European Countries (European Patent Office)

2015 Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering

2015 Hoover Medal (American Society of Mechanical Engineers)

2015 Scheele Award (Swedish Pharmaceutical Society)

2015 Kazemi Award for Research Excellence in Biomedicine

2015 Honorary Degree, University of Maryland

2015 Honorary Degree, Hanyang University (South Korea)

2015 Honorary Degree, University of New South Wales (Australia)

2015 Cornell Entrepreneur of the Year

2014 Kyoto Prize in Advanced Technology

2014 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences

2014 Biotechnology Heritage Award (Chemical Heritage Foundation)

2014 Chemical Pioneer Award (American Institute of Chemists)

2014 Honorary Degree, Drexel University

2014 Honorary Degree, University of Western Ontario (Canada)

2014 ETH Zurich Chemical Engineering Medal

2014 Elected a Foreign Corresponding Member of the Austrian Academy

of Sciences

2014 Mack Memorial Award (Ohio State University)

2013 Wolf Prize in Chemistry (Wolf Foundation)

2013 United States National Medal of Technology and Innovation (for 2011)

2013 RUSNANOPRIZE International Prize in Nanotechnology

2013 Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science

2013 Distinguished Investigator Award (American College of Clinical Pharmacology)

2013 Honorary Fellow Award (American College of Clinical Pharmacology)

2013 Honorary Degree, Boston University

2013 Honorary Degree, Tel Aviv University

2013 Honorary Degree, Ben Gurion University

2013 Julio Palmaz Award for Innovation in Healthcare and the Biosciences

(BioMed SA)

2013 Industrial Research Institute Medal

2013 IEEE Medal for Innovations in Healthcare Technology

2013 Founders Award (Society of Biomaterials)

2013 MDEA Lifetime Achievement Award

2012 Scientist of the Year (R&D Magazine)

2012 Elected to National Academy of Inventors (Charter Fellow)

2012 Priestley Medal (American Chemical Society)

2012 Perkin Medal (Chemical Heritage Foundation)

2012 Terumo International Prize (Japan)

2012 Wilhelm Exner Medal (Austria)

2012 Fellow, American Institute of Chemical Engineers

2012 Feodor Lynen Award (Nature Biotechnology)

2011 Economist Innovation Award for Bioscience

2011 Warren Alpert Foundation Prize (Warren Alpert Foundation/

Harvard Medical School)

2011 Walker Prize (Boston Museum of Science)

2011 Apple Award (American Spinal Injury Association/Shepherd Center/

Thomas Land Publishers Inc.)

2011 Honorary Degree, Bates College

2011 Frontier of Science Award (Society of Cosmetic Chemists)

2011 Fellow (American Chemical Society)

2010 Elected International Fellow (Royal Academy of Engineering)

2010 Founders Award (National Academy of Engineering)

2010 Honorary Degree, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

2010 Honorary Degree, Willamette University

2010 Robert Flectcher Award (Thayer School of Engineering, Dartmouth College)

2010 EMBS Academic Career Achievement Award

(IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society)

2010 Elected to the Controlled Release Society College of Fellows

2010 Founding POLY Fellow (Division of Polymer Chemistry,

American Chemical Society)

2009 Honorary Degree, Harvard University

2009 University of California at San Francisco Medal

2009 Honorary Degree, Mount Sinai School of Medicine

2009 Distinguished Chemist Award (New England Institute of Chemists)

2009 Biomedical Research Leaders Award (Massachusetts Society

for Medical Research)

2008 Millennium Technology Prize

2008 Max Planck Research Award

2008 Prince of Asturias Award for Technical and Scientific Research

2008 Elected Foreign Academic Member (Royal Academy of Pharmacy of Spain)

2008 Founders Award (American Institute for Chemical Engineers)

2008 Innovation in Health and Technology Award (Boston History and

Innovation Collaborative)

2008 Acta Biomaterialia Gold Medal (Acta Materialia)

2008 Named one of the 100 Top Chemical Engineers of the 20th Century (AIChE)

Langer_Academy_1560 Laura-Langer 2017 Breakthrough Prize

2007 United States National Medal of Science (for 2006)

2007 Chemistry of Materials Award (American Chemical Society)

2007 Herman F. Mark Award (American Chemical Society,

Polymer Chemistry Division)

2007 Honorary Degree, Yale University

2007 Wenig Memorial Award for Outstanding Achievement in Drug Delivery

2007 First Prize of Scientific Award (BMW Group)

2007 Elected to the Biotechnology Hall of Fame

2006 Elected to the National Inventors Hall of Fame

2006 Honorary Degree, Northwestern University

2006 Honorary Degree/Commencement Address, Albany Medical College

2006 Bailey Award (American Institute of Chemical Engineers)

2005 Von Hippel Award (Materials Research Society)

2005 Albany Medical Center Prize in Medicine and Biomedical Research

2005 Dan David Prize (Materials Science)

2005 Honorary Degree, Uppsala University

2005 Honorary Degree/Commencement Address, Pennsylvania State University

2005 Honorary Degree, University of Nottingham

2005 Lifetime Achievement Award (Society for In Vitro Biology)

2005 Rainer Hoffmann Product through Science Award (Controlled Release Society)

2005 Technology Innovation and Development Award (Society of Biomaterials)

2005 Washington Award (Western Society of Engineers)

2004 Charles F. Kettering Prize (General Motors Cancer Research Foundation)

2004 Nelson Taylor Award (Pennsylvania State University)

2003 Heinz Award for Technology, Economy and Employment

2003 Harvey Prize in Science and Technology and Human Health

2003 John Fritz Medal (American Association of Engineering Societies)

2003 Elected to the Academy of Achievement (Golden Plate Award)

2003 Honorary Degree, University of Liverpool, England

2002 Dickson Prize for Science (Carnegie Mellon University)

2002 Charles Stark Draper Award (National Academy of Engineering)

2002 Othmer Gold Medal (Chemical Heritage Foundation)

2002 Nagai Innovation Award (Controlled Release Society)

2002 Honorary Degree, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

2002 Herman Schwan Award (University of Pennsylvania)

2001 Harrison Howe Award (American Chemical Society)

2000 Honorary Degree, Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium

2000 Glaxo Wellcome International Achievement Award (Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain)

2000 Millennial Pharmaceutical Scientist Award (Millennial World Congress of Pharmaceutical Sciences)

2000 First Pierre Galletti Award (American Institute of Medicine &

Biological Engineering)

2000 Wallace Carothers Award (American Chemical Society, Delaware Section)

1999 American Chemical Society Award in Polymer Chemistry

1999 Esselen Award (American Chemical Society, Northeast Section)

1999 Ebert Prize (American Pharmaceutical Association)

1999 G.N. Lewis Medal (University of California at Berkeley)

1998 Outstanding Pharmaceutical Paper Award (Controlled Release Society)

1998 Lemelson-MIT Prize for Invention and Innovation

1998 The Nagai Foundation Tokyo International Prize

1997 Killian Faculty Achievement Award (MIT)

1997 Wiley Medal (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

1997 Honorary Degree, Technion - Israel

1996 Canada Gairdner International Award (Canada Gairdner Foundation)

1996 Honorary Degree, Eidgenossische Technische Hochschule-ETH, Switzerland

1996 William Walker Award (American Institute of Chemical Engineers)

1996 Society of Plastics Engineers International Award

1996 Ebert Prize (American Pharmaceutical Association)

1996 Elected a Fellow of Biomaterials Science and Engineering

1996 Avis Distinguished Visiting Professor (University of Tennessee)

1995 International John W. Hyatt Service to Mankind Award

(Society of Plastics Engineers)

1995 Ebert Prize (American Pharmaceutical Association)

1995 Elected a Fellow (American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists)

1995 PEL Associates Award (PEL Associates, Groton, Connecticut)

1994 Elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

1994 Elected a Fellow, Society of Biomaterials

1993 Distinguished Pharmac. Scientist Award (Highest Honor of the Amer.

Assoc. of Pharm. Scient.)

1992 Elected to the National Academy of Sciences

1992 Elected to the National Academy of Engineering

1992 American Chemical Society Award for Applied Polymer Science

(Phillips Award)

1992 Elected a Founding Fellow, American Institute of Medical and

Biological Engineering

1992 Outstanding Pharmaceutical Paper Award (Controlled Release Society)

1992 Perlman Memorial Award (American Chemical Society,

Biochemical Technology Division)

1991 Organon Teknika Award (European Society for Artificial Organs)

1991 Charles M.A. Stine Award in Materials Science and Eng.

(American Institute of Chemical Engineers)

1990 Professional Progress Award (American Institute of Chemical Engineers)

1990 Clemson Award for Basic Research (Society for Biomaterials)

1990 Outstanding Pharmaceutical Paper Award (Controlled Release Society)

1989 Elected to the National Academy of Medicine

1989 Creative Polymer Chemistry Award (American Chemical Society,

Polymer Division)

1989 Outstanding patent in Massachusetts and one of the twenty

outstanding patents in the U.S. (Intellectual Property Owners, Inc.)

1989 Founders Award for Outstanding Research (Controlled Release Society)

1988 Elected to the Gordon Conference Research Council

1988 Elected Chairman, Gordon Conference on Drug Carriers in Biology and Medicine

1986 Food, Pharmaceutical and Bioengineering Award

(American Institute of Chemical Engineers)

1983 Outstanding Paper, Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineering

1982 Paper Listed as One of the Outstanding Papers of the Year, CHEMTECH

1982 Recipient of the first Dorothy W. Poitras Chair, MIT

1982 Outstanding Teacher Award, MIT Graduate Student Council

성용길 미국 유타대학 연구교수(본지 미주지역본부 회 science@nobelscience.co.kr

<저작권자 © 노벨사이언스, 무단 전재 및 재배포 금지>

간단한 공정으로 이산화탄소 분리 성공

간단한 공정으로 이산화탄소 분리 성공